The news is clear: The economic recovery has not been felt equally by communities across the country. Black men are routinely excluded from the labor force, and Black women in particular saw their employment gap widen at the end of last year. Unfortunately, these trends aren't recent developments. Organizations and individuals continue the ongoing fight for economic equity, but Black leaders are often overlooked in their varied approaches to help rectify longstanding racial disparities in hiring practices, career trajectories, and financial mobility.

Explore the views and legacies of 5 Black economists and activists who played key roles in shaping our views on work and positively impacting the experience of African Americans in the workplace.

Dr. Sadie T. M. Alexander

The first African American to receive a Ph.D. in economics, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander came from a family of lawyers, academics, artists, and community leaders. “Every one of them faced down hatred and bigotry to achieve success. Sadie could do no less." When she was unable to find work as an economist due to her race, she went back to school as the first African American woman to enroll in the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Law. Joining her husband’s law practice, they advocated for civil rights gains in their hometown of Philadelphia and joined national organizations and campaigns.

Remembered mostly for her legal work and activism, her impact as an economist has come to the forefront recently through associations and conferences held in her honor. She also deeply influenced modern economist Nina Banks from Bucknell University, who “spent years researching the archive … to uncover the economic ideas within her words” and edited a collection of Dr. Alexander’s speeches and writings.

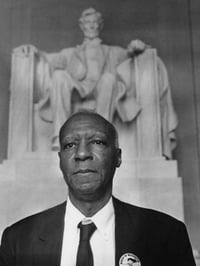

A. Philip Randolph

Growing up “in an intellectual household” in Florida as the son of a preacher in the AME Church, Asa Philip Randolph moved to Harlem in 1911. Influenced by W.E.B. DuBois, a sociologist and activist with groundbreaking approaches and views that often put him at odds with more conservative counterparts, Randolph adopted socialist political views. This “led to a job working for the Brotherhood of Labor, an employment agency for Black workers.” His continued social activism in support of labor rights culminated in “a 10-year drive to organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP).”  Commonly known as Pullman porters, these railcar attendants were mostly Black workers paid far less than their white counterparts. The BSCP became the first majority African American labor union in the country.

Commonly known as Pullman porters, these railcar attendants were mostly Black workers paid far less than their white counterparts. The BSCP became the first majority African American labor union in the country.

Randolph continued advocating for fair labor practices, bringing “the gospel of trade unionism to millions of African American households.” In 1963, he conceived of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Over 200,000 demonstrators traveled to the nation’s capital that August to champion stronger civil rights legislation and increased access to jobs. The event is most famous nowadays as the site of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Russell Lasley

Leading the next generation of labor reformers was Russell Lasley, a worker at The Rath Packing Company who later became Vice-President of the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) and “rose to become one of the central figures in the American civil rights movement.” Formed in the 1940s, UPWA was a progressive organization that tackled discrimination in their members’ professional and social spheres.

As a union leader, Lasley fought unfair housing practices in Chicago, “trying to open up housing for black families in white neighborhoods.” Due to the UPWA’s intrinsic focus on civil rights and equity for all members, it was “extraordinary” in that white members often would join in the fight to support their Black coworkers.

Addie Wyatt

Another product of the UPWA was Addie Wyatt, a worker at Armour and Company. When she was “replaced with a white worker who was paid more,” the union fought this blatant violation of her contract’s non-discrimination clause and got her reinstated. This inspired Wyatt to become a more active member of the UPWA: “I didn’t know what the union was. But I know that I needed help and here was the place that I could get that help. I knew that I wanted to help other workers, and I found out that I could help them by joining with them and making the union strong and powerful enough to bring about change.”

Seen as a leader in the labor movement, she became president of the UPWA in 1956 and joined multiple key marches and demonstrations in the Civil Rights Movement. Eventually, she co-founded the Coalition of Labor Union Women, the only organization for union women in the US, and the National Organization of Women. In 2012, she became an inductee into the Department of Labor’s Hall of Honor.

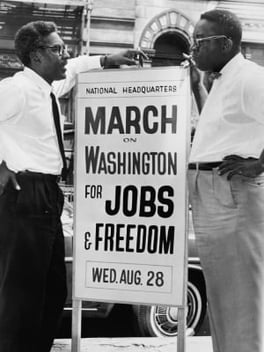

Bayard Rustin

Known by most as a Black LGBTQ pioneer, Bayard Rustin (pictured below, left) influenced key events in the fight for labor fairness and was instrumental in the passing of Executive Order 8802, which established the Fair Employment Practices Committee. Rustin was also a trusted advisor to Dr. King throughout the mid-20th century. Born in suburban Pennsylvania, his Quaker upbringing and family life sparked a “commitment to nonviolence” that aligned with the Kings’ philosophies.

As a leader in the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Congress of Racial Equality, Rustin organized and joined in several marches and nonviolent demonstrations during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. And in 1963, working closely with A. Philip Randolph, he brought the latter’s idea to life and organized the March on Washington to call for “equal rights for everyone–whether they were black or white, rich or poor, Muslim or Christian.”

As a leader in the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Congress of Racial Equality, Rustin organized and joined in several marches and nonviolent demonstrations during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. And in 1963, working closely with A. Philip Randolph, he brought the latter’s idea to life and organized the March on Washington to call for “equal rights for everyone–whether they were black or white, rich or poor, Muslim or Christian.”

Because of his sexuality, Rustin was harassed, threatened, arrested, and often silenced. To this day, many are unaware of the contributions of the “lost prophet” of the Civil Rights Movement, as he was ousted from many leadership positions and relegated to the background in official narratives. Working behind the scenes, however, he “overcame and made a huge impact on the civil and economic rights movements” for workers, African Americans, and the LGBT community.

Learn more:

These five leaders all fought societal battles across multiple fronts. We know issues of labor, race, gender, and economics are often intertwined, and we’re pausing this month to recognize and appreciate the tireless work of individuals and organizations striving for economic equity in the workplace and workforce development.

Get to know more African American leaders in economics and labor rights.

Hear what Black labor activists and policy advocates are saying in response to the pandemic.

Discover why our modern workforce needs Black labor leaders.